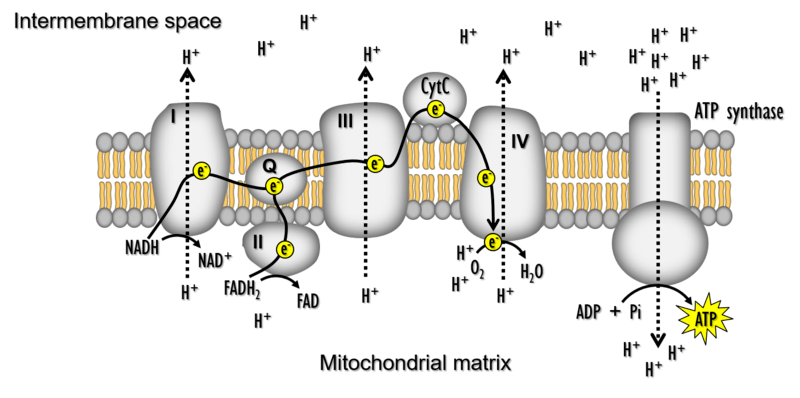

Mitochondria are fundamental to life. In what has been termed “the fire of life”, mitochondria use O2 and metabolic fuels to produce most of the ATP cells need to function during the process of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Mitochondria are also a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are produced when electrons leak from their usual route through the electron transport system (ETS). ROS were long regarded as harmful byproducts of mitochondria that damage cell components, but they are now known to have many important roles in cell signalling. There is growing appreciation that the functions of mitochondria in energy production, ROS homeostasis, and various other cellular process underlie aerobic performance, responses to environmental change, and many other key features of animal biology.

Aerobic performance is determined by the capacity of mitochondria in active tissues to consume O2 and produce ATP. This is determined by both the abundance of mitochondria within active tissues (‘mitochondrial quantity’) and the functional properties of those mitochondria (‘mitochondrial quality’). We use various techniques to examine how changes in mitochondrial quantity and quality contribute to variation in aerobic performance and the ability to cope in challenging environments.

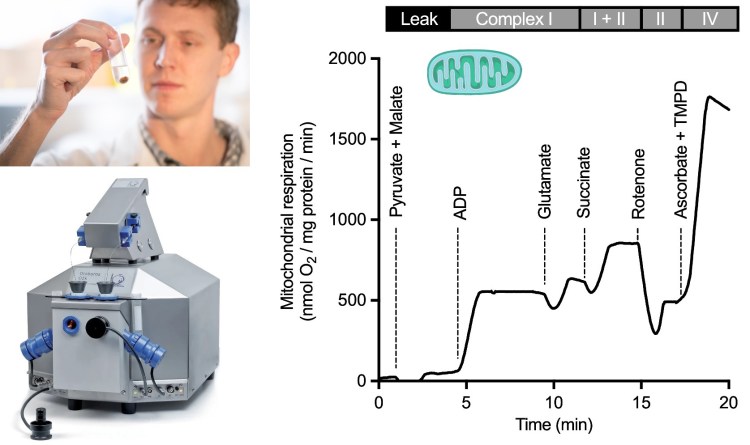

Mitochondrial physiology is studied by high-resolution respirometry and fluorometry using various preparations, including isolated mitochondria (top left; former PDF Neal Dawson shown) and permeabilized tissues. Specific mitochondrial substrates, uncouplers, and inhibitors are used to examine different states of leak, oxidative phosphorylation, and electron transport (right) (Scott et al. 2018).

Mitochondrial abundance and structure can be measured using electron microscopy. Striated muscles contain distinct subpopulations of mitochondria: subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SSM) near the cell membrane and capillaries (shown with red shading), and intermyofibrillar mitochondria (IMM) deeper in the cell.

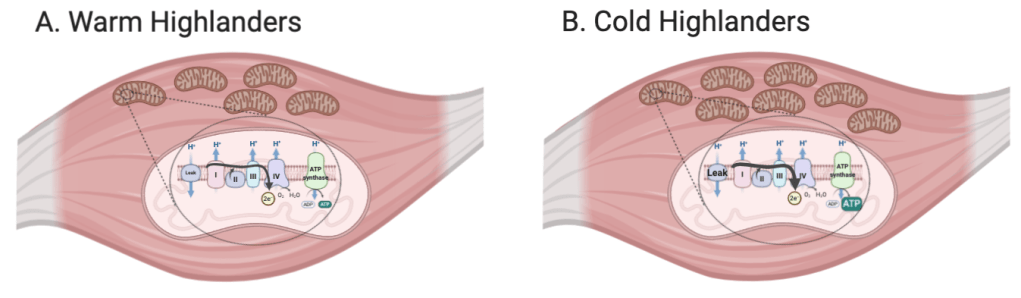

We are using a comparative approach with deer mice to examine how phenotypic plasticity and/or evolutionary adaptation to high altitude has altered mitochondrial physiology (see Comparative & Evolutionary Physiology for a description of our lab colonies and experimental manipulations). Our work has shown that exposure to the cold and hypoxic environment at high altitude leads to plastic adjustments in mitochondrial physiology that increase oxidative capacity in thermogenic tissues. High-altitude populations of deer mice have also evolved increased oxidative capacity and mitochondrial O2 affinity in skeletal muscles compared to low-altitude populations. Ongoing research is working to uncover the mechanisms of these changes, to examine how changes in mitochondrial physiology contribute to ROS homeostasis, and to elucidate the signalling mechanisms responsible for adjusting mitochondrial metabolism.

Our work in birds has shown that common changes in mitochondrial physiology and metabolism have arisen across many species at high altitude. Some evolved changes in mitochondrial physiology depend on the duration of evolutionary time at high altitude, with the most pronounced changes exhibited in the most established species.

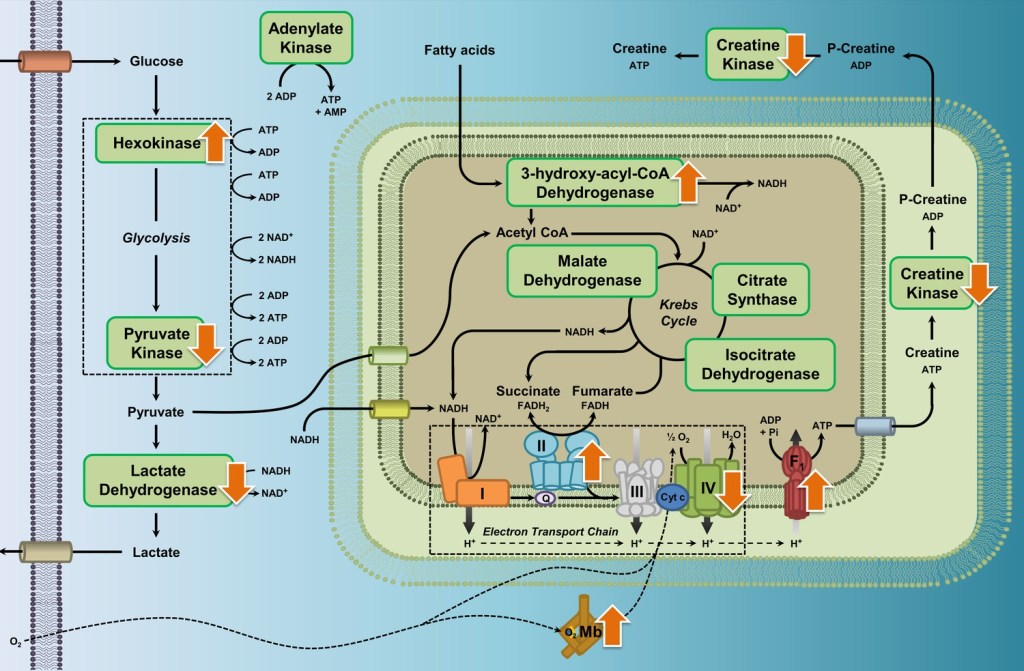

Common differences in metabolic enzyme activities and myoglobin content in the flight muscle were observed across several species of high-altitude waterfowl compared to their close relatives from low altitudes, shown as orange arrows in the figure above (Dawson et al. 2020).